Extending the shelf life of bitterness

on the habit of preserving grudges

When my father was in his 80s, he met his cousin at a carwash south of Wilmington. The man said, “Aren’t you Bob Hickman?” This was one of their only meetings in their adult lives. It raises the question: how could these two Hickman cousins, both living in Wilmington their entire lives, be such strangers? Part of the answer goes back to their respective fathers in the early 1900s.

The two brothers, Emmett Stewart and Frank Forrest Hickman, both businessmen in Wilmington, became permanently estranged over a money issue of some sort. Their families never interacted.

In my sister Martha’s Ancestry Journal she recalls another tragic estrangement:

And for some reason Emmett’s father Westley was not allowed to visit Emmett and Ethel’s home when Dad was young. In order to see Dad from time to time, Westley would stop by the school yard to chat and offer treats, sometimes coming at the end of the school day to walk with Dad, presumably only part of the way home. I think that’s one of the saddest family stories I have heard.

The source of that rift was never clear.

What is gained by the stoking of grudges and grievances? Why is the landscape of forgiveness often so difficult to traverse? I invoke the phrase “Life is too short” when I hear stories of endless and senseless enmity. In fact, Emmett had a chronic heart condition and died at age 57, four years before I was born. I never met my namesake. Frank also died young — 54, of a heart attack.

In her advice column in the Washington Post (“Wedding is new front in the cold war with late wife’s sister” September 3, 2025) Carolyn Hax urges the widower “not to do anything to extend the shelf life of the bitterness” between the parties. It is a brilliant image. I picture a jar on the pantry shelf of my mind, preserving a memory of an affront, an unforgivable trespass, a cruel text — any past event that triggered in my little heart a sense of grievance — any of a series of thoughts that begin with:

“How dare she…”

“I’ll give him an earful next time I…”

“I won’t rest until justice is served…”

“Nobody treats me like this and gets away with it.”

I guess you could call it “self-righteous anger.” It is a very powerful emotion, one that we see on display in the news every day.. The media is so unfair. No one has been treated worse than me. The deep state is the enemy within. The people who attack me are sick individuals.

The artifice of victimhood is on full display. For some reason, admitting that you are a victim has a cast of virtue in politics these days. Sharing your victimhood publicly also serves to expand the circle of people willing to support your pursuit of retribution. Anyone can engage in this behavior on any scale, because it serves some basic need. We share our grievances with others with the hope that they share our indignation and take our side–which gives us further validation that we are right. And maybe we get a little sympathy in the mix. It’s infectious.

Holding a grievance is like slow-burn anger. It represents power at a very basic level: I am ready to fight!! I don’t have to fight, but I am ready, right now. I’m writing the script for how I will express my disdain in some future meeting. And for however long I hold onto this grudge, I prepare my hammer of righteousness to strike a blow. I am in some kind of control even without saying a word or doing anything. I am determined to extend the shelf life of my bitterness.

Then it occurred to me that “bringing the hammer down” — making clear to the offending party the magnitude of their violation, how and for how long their antics have weighed on me, including a complete tally of the cost to me of their offense — would only possibly make me feel better and would definitely make them feel worse.

Another alternative exists — forgiveness. Highly prized in many religions for millennia, it’s given less media attention and definitely does not carry the “punch” of aggrievement and victimhood.

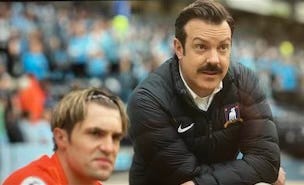

The Ted Lasso Apple TV series features many examples of forgiveness. Lasso, a Kansas football coach transplanted to the UK to coach football (soccer). He arrives at his new job with his unassuming mid-western charm, generous spirit, good-natured humor, and zen-like wisdom. In the highly competitive environment of Premier League football, Lasso is eternally optimistic and sees his job as helping the players be their best selves, on and off the field.

We find out that super-star forward Jamie Tartt grew up with an emotionally and physically abusive father. Jamie’s accomplishments on the field never earned his father’s praise. Nothing he did was good enough–which probably accounted in part for his amazing success as a player: that and his anger at his father for all those years of misery.

In a Season 3 episode, Lasso notices Jamie’s energy flagging at a critical point in the game. They were playing their rival Manchester at the end of the season. At one timeout, Jamie was on the sidelines scanning the bleachers, apparently looking for his nemesis.

Lasso: When was the last time you saw your dad?

Jamie: Wembley

L: Y’all talk since then?

J: Nope.

L: Ok, well if you could talk to him right now, what would you say?

J: I’d say, “F— you.”

L: Yeah. Makes sense. Anything else?

J: Yeah. I’d say… (pausing, looking up at Lasso) …“Thank you.”

L: You know, Jamie, if hating your Pops ain’t motivating you like it used to, it might be time to try something different. Just forgive him.

J: F— no. I ain’t giving him that.

L: No. You ain’t giving him anything. When you choose to do that, you’re giving that to yourself.

I have had a real-life encounter with this idea of forgiveness being a choice. Without going into detail, let’s say it was a kind of misunderstanding that turned into a pattern of offense that resulted in my trust being drained from the relationship. I identified as the aggrieved party for years, and the abuse was the subject of discussion in our circle.

Then I received a kind note from a friend reminding me of three truths:

1) Past choices are in the past — we cannot undo them..

2) We cannot control what others say or do.

3) Forgiveness is essential, we can choose to do it, and the act of forgiving benefits the forgiver.

In my return email I said that forgiving was on the path of my journey but that I was not “there yet.”

For two days I pondered what I meant by that. What was going to happen that would bring me to the point of being able to forgive? When and how would I “get there”?

My conclusion: there was nothing within my agency that would get me there. I was either there, or not there.

“Do or do not. There is no try,” Yoda reminds us.

Words fail me here. But when I reached that conclusion, and “made the choice” to forgive, there was a lightness, a buoyancy. An equanimity.

A sense of reclaiming acres of my internal landscape that had been overtaken by the kudzu of grievance: scripts in which I reproach the offenders, soliloquies to no one about my indignation. Bitter vines.

All this clutter disappeared. Nothing had changed, yet everything was different.

Forgiveness doesn’t excuse or erase the past, but it does reclaims space in the soul that bitterness once occupied.

What other jars are sitting in the pantry of my mind, waiting to be opened and dismissed? How can I practice this task of forgiveness, even on the smallest things, with relationships that matter? What generational strength might accrue if I do this – embrace the more graceful path of peace and forgiveness?

Thank you Stew! Such an important message for these times. For all times.

Thank you. Beautiful post. I used to be quite a grudge holder. I'm much better than I used to be, but still a work in progress! xo